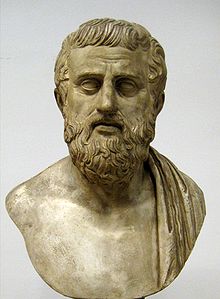

Philoktetes

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

Odysseus

Chorus

Trader (Spy)

Neoptolemos

Philoktetes

Herakles

PHILOKTETES

ODYSSEUS

This is the shore of jagged Lemnos,

a land bound by waves, untrodden, lonely.

Here I abandoned Poias's son,

Philoktetes of Melos, years ago.

Neoptolemos, child of Lord Achilles,

the greatest by far of our Greek fighters,

I had to cast him away here:

our masters, the princes, commanded me to,

for disease had conquered him, and his foot

was eaten away by festering sores.

We had no recourse. At our holy feasts,

we could not reach for meat and wine.

He would not let us sleep;

he howled all night, wilder than a wolf.

He blanketed our camp with evil cries,

moaning, screaming.

But there is no time to talk of such things:

no time for long speeches and explanations.

He might hear us coming

and foil my scheme to take him back.

Your orders are to serve me,

to spy out the cave I found for him here---

a two-mouthed cave, exposed to the sun

for warmth in the cold months,

admitting cool breezes in summer's heat;

to the left, nearby it, a sweet-running spring,

if it is still sweet.

If he still lives in this cave or another place,

then I'll reveal more of my plan.

Listen: both of us have been charged with this.

NEOPTOLEMOS

Lord Odysseus, what you speak of is indeed nearby.

This is his place.

ODYSSEUS

Where? Above or below us? I cannot tell.

NEOPTOLEMOS

Above, and with no sound of footsteps or talking.

ODYSSEUS

Go and see if he's sleeping inside.

NEOPTOLEMOS

I see an empty dwelling. There is no one within.

ODYSSEUS

And none of the things that distinguish a house?

NEOPTOLEMOS

A pallet of trampled leaves, as if for a bed.

ODYSSEUS

And what else? Is there nothing more inside the cave?

NEOPTOLEMOS

A wooden mug, carelessly made,

and a few sticks of kindling.

ODYSSEUS

So this is the man's empty treasure-vault.

NEOPTOLEMOS

Look here. Rags lie drying in the sun,

full of pieces of skin and pus from his sores.

ODYSSEUS

Then clearly he still lives here.

He can't be far off.

Weakened as he is by long years of disease,

he can't stray far from home.

He is probably out scratching up a meal

or an herb he knows will relieve his pain.

Send a guard to keep close watch on this place

so he doesn't take me by surprise--

for he'd rather have me than any other Greek.

NEOPTOLEMOS

The path will be guarded.

Now tell me the rest.

ODYSSEUS

Son of Achilles, we are here for a reason.

You must be like your father, and not in strength alone.

If any of this sounds strange to you,

no matter. You must still serve those who are over you.

NEOPTOLEMOS

What must I do?

ODYSSEUS

Entangle Philoktetes with clever words.

In order to trick him, say, when he asks you,

"I am Achilles's son"--there's no lie in that--

say you're on your way back home,

that you have abandoned the Greeks and all their ships,

you hate them so.

Speaking to him piously, as though to the gods of Olympos,

tell him they convinced you to leave your home,

by swearing that you alone could storm Troy.

And when you claimed your dead father's weapons,

as is your birthright, say they scorned you,

called you unworthy of them, and gave them to me,

although you had been demanding them. Say whatever you want to

against me. Say the worst that comes to mind.

None of it will insult me. If you do not match this task,

you will cast endless sorrow and suffering on the Greeks.

If we do not return with this poor man's bow,

you will not take the holy city of Troy.

You may wonder whether you can do this safely,

and why he would trust you. I'll tell you why:

you have come here willingly, without having been forced,

and you had nothing to do with what happened before.

I cannot say the same.

If Philoktetes, bow in hand, should see me,

I would be dead in an instant.

So would you, being in my company.

We must come up with a scheme.

You must learn to be cunning,

and steal away his invincible bow.

I know, son, that by nature you are unsuited

to tell such lies and work such evil.

But the prize of victory is a sweet thing to have.

Go through with it. The end justifies the means, they'll say.

For a few short, shameless hours, yield to me.

From then on you'll be hailed as the most virtuous of men.

NEOPTOLEMOS

Son of Laertes, what pains me to hear

pains me more to do. It is not my nature, as you say,

to take what I want by tricks and schemes.

My father, as I hear it, was of the same mind.

I will gladly fight Philoktetes, capture him,

and make him our hostage, but not like this.

How can a one-legged man, alone, win against us?

I know I was sent to carry out these orders.

I do not want to make things hard for you.

But I far prefer failure, if it is honest,

to victory earned by treachery.

ODYSSEUS

You are the son of a great and noble man.

When I was young, I held my tongue back

and let my hand do my work.

Now, as you're tested by life--as men live it--

you will see as I have that everywhere

it is our words that win, and not our deeds.

NEOPTOLEMOS

What are your orders, apart from telling lies?

ODYSSEUS

I order you to capture him,

to take him with trickery, however deceitful.

NEOPTOLEMOS

And why not by persuasion

after telling him the truth?

ODYSSEUS

Persuasion is impossible. So is force.

NEOPTOLEMOS

Is he so sure of his strength?

ODYSSEUS

Yes, if he carries his unswerving arrows,

black death's escorts.

NEOPTOLEMOS

Even to meet him, then, is unsafe.

ODYSSEUS

Not if you win him over by guile,

as I have said.

NEOPTOLEMOS

And you do not find such lying disgusting?

ODYSSEUS

Not if a lie ends with our salvation.

NEOPTOLEMOS

How could one say such things

and keep a straight face?

ODYSSEUS

What you do is for our gain.

He who hesitates is lost.

NEOPTOLEMOS

What good would it do me for him to come to Troy?

ODYSSEUS

Only Philoktetes can conquer the city.

NEOPTOLEMOS

Then I will not take it after all,

as I have been promised.

ODYSSEUS

Not without his arrows, nor they without you.

NEOPTOLEMOS

Then I must have them, if what you say is true.

ODYSSEUS

You will bring back two prizes, if only you'll act.

NEOPTOLEMOS

What are they? If I know,

I will not refuse the deed.

ODYSSEUS

You will be called wise because of your trick,

and brave for the sack of Troy.

NEOPTOLEMOS

Then let it be so. I will do what you order,

putting aside my sense of shame.

ODYSSEUS

Do you remember all the counsel I have given?

NEOPTOLEMOS

Every word of it. I will follow it all.

ODYSSEUS

Stay here at the cave and wait for him.

I will leave so he doesn't know I have been here.

I will take the guard and go back to the ship;

if I think you're in trouble I will send him back,

disguised as a merchant sailor, a captain.

Whatever story he tells you, use it to advantage.

I am going now. The rest is up to you.

May our guides be Hermes, who instructs us in guile,

and Athena, goddess of victory, goddess of our cities,

who aids me at all times.

CHORUS

I am a stranger in a foreign land.

What shall I say to Philoktetes? What shall I hide?

Tell me. Knowledge that surpasses all others' knowledge

and greatest wisdom falls to him who rules

with Zeus's divine scepter.

To you, child, this ancient strength has come,

all the power of your ancestors. Tell me

what must be done to serve you well.

NEOPTOLEMOS

Look now, without any fear:

he sleeps on the seacliff,

so take courage.

When he awakes it will be terrible.

Muster up your courage, and aid me then.

Follow my lead. Help as you can.

CHORUS

As you command, my lord Neoptolemos.

My duty to you is always first in my thoughts.

My eye is fixed on your best interests.

Now show me the place that he inhabits,

and where he sleeps.

I should know this lest he take me in ambush.

I am frightened and yet fascinated,

as though by a snake or a scorpion's lair.

Where does he live? Where does he sleep?

Where does he walk?

Is he inside or outside?

NEOPTOLEMOS

Look. You will see a cave with two mouths.

That is his house.

That is his rocky sleeping-place.

CHORUS

Where is he now, the unlucky man?

NEOPTOLEMOS

It is clear to me that he claws his way

to find food nearby.

He struggles now to bring down birds with his arrows,

to fuel this wretched way of life.

He knows no balm to heal his wounds.

CHORUS

I pity him for all his woes,

for his distress, for his loneliness,

with no countryman at his side;

he is accursed, always alone,

brought down by bitter illness;

he wanders, distraught,

thrown off balance by simple needs.

How can he withstand such ceaseless misfortune?

O, the violent snares laid out by the gods!

O, the unhappy human race,

living always on the edge,

always in excess.

He might have been a well-born man,

second to none of the noble Greek houses.

Now he has no part of the good life,

and he lies alone, apart from others,

among spotted deer and shaggy, wild goats.

His mind is fixed on pain and hunger.

He groans in anguish,

and only a babbling echo answers,

poured out from afar,

in answer to his lamentations.

NEOPTOLEMOS

None of this amazes me.

It is the work of divine Fate,

if I understand rightly.

Savage Chryse set these sufferings on him,

the share of sufferings he must now endure.

His torments are not random.

The gods, surely, must heap them on him,

so that he cannot bend the invincible bow

until the right time comes, decreed by Zeus,

and as it is promised, Troy is made to fall.

CHORUS

Be quiet, boy.

NEOPTOLEMOS

What is it?

CHORUS

A clear groan---

the steadfast companion of one walking in pain.

Where is it?

Now comes a noise:

a man writhes along his path,

from afar comes the sigh of a burdened man---

the cry has carried.

Pay attention, boy.

NEOPTOLEMOS

To what?

CHORUS

To my second explanation. He is not so far away.

He is inside his cave. He is not walking abroad

to his panpipe's doleful song,

like a shepherd wandering with his flocks.

Rather he has bumped his wounded leg and shouts

as if to someone far away,

as if to someone he has seen at the harbor.

The cry he makes is terrible.

PHILOKTETES

You there, you strangers:

who are you who have landed from the sea

on an island without houses or fair harbor?

From what country should I think you,

and guess it correctly? You look Greek to me.

You wear Greek clothes, and I love to see them.

I want to hear you speak my tongue.

Do not shun me, amazed

to face a man who has become so wild.

Pity one who is damned and alone,

wasted away by his sufferings.

Speak. Speak, if you come as friends.

Answer me. It is unreasonable

not to answer each other's questions.

NEOPTOLEMOS

We are Greeks. You wanted to know.

PHILOKTETES

O, beloved tongue! I understand you!

That I should hear Greek words after so many years!

Who are you, boy? Who sent you? What brought you?

What urged you here? What lucky wind?

Answer. Let me know who you are.

NEOPTOLEMOS

My people are from wavebound Skyros, an island.

I am sailing homeward.

I am called Neoptolemos, Achilles's son.

Now you know everything.

PHILOKTETES

Son of a man whom I once loved,

son of my beloved country,

nursed by ancient Lykomedes---

what business brought you here?

Where is it that you sail from?

NEOPTOLEMOS

I sail from Troy.

PHILOKTETES

What? You sail away from Troy?

You were not there with us at the start.

NEOPTOLEMOS

Did you take part in that misery?

PHILOKTETES

Then you do not know who stands before you?

NEOPTOLEMOS

I have never seen you before. How could I know you?

PHILOKTETES

You do not know my name?

The fame my woes have given me?

The men who brought me to my ruin?

NEOPTOLEMOS

You see one who knows nothing of your story.

PHILOKTETES

Then I am truly damned. The gods must surely hate me

for not even a rumor to have come to Greece

of how I live here.

The wicked men who abandoned me

keep their secret, then, and laugh,

while the disease that dwells within me grows,

and grows stronger.

My son, child of great Achilles,

you may yet have heard of me somehow:

I am Philoktetes, Poias's son,

the master of Herakles's weapons.

Agamemnon, Menelaos, and Odysseus

marooned me here, with no one to help me,

as I wasted away with a savage disease,

struck down by a viper's hideous bite.

After I was bitten, we put in here

on the way from Chryse to rejoin the fleet

and they cast me ashore.

After our rough passage, they were glad to see me

fall asleep on the seacliffs, inside this cave.

Then they went off, leaving with me

rags and breadcrumbs, and few of each.

May the same soon befall them.

Think of it, child: how I awoke

to find them gone and myself left alone.

Think of how I cried, how I cursed myself,

when I knew my ship had gone off with them,

and not a man was left to help me

overcome this illness.

I could see nothing before me but grief and pain,

and those in abundance.

Time ran its course.

I have had to make my own life,

to be my own servant in this tiny cave.

I seek out birds to fill my stomach,

and shoot them down.

After I let loose a tautly drawn bolt,

I drag myself along on this stinking foot.

When I had to drink the water that pours from this spring,

in icy winter, I had to break up wood,

crippled as I am,

and melt the ice alone.

I dragged myself around and did it.

And if the fire went out, I had to sit,

and grind stone against stone

until a spark sprang up to save my life.

This roof, if I have fire, at least gives me a home,

gives me all that I need to stay alive

except release from my anguish.

Come, child, let me tell you of this island.

No one comes here willingly.

There is no anchorage here, nor any place

to land, profit in trade, and be received.

Intelligent people know not to come here,

but sometimes they do, against their will.

In the long time I have been here, it was bound to happen.

When those people put in, they pitied me---

or pretended to, at least---and gave me new clothes

and a bit of food. But when I asked for a homeward passage,

they would never take me with them.

It is my tenth year of hunger and the ravaging illness

that I feed with my flesh.

The Atreids and Odysseus did this to me.

May the Olympian gods give them pain in return.

CHORUS

I am like those who came here before.

I pity you, unlucky Philoktetes.

NEOPTOLEMOS

And I am a witness to your words.

I know you speak truly, for I have known them,

the evil Atreids and violent Odysseus.

PHILOKTETES

Do you too have a claim

against the all-destroying house of Atreus?

Have they made you suffer? Is that why you are angry?

NEOPTOLEMOS

May the anger I carry be avenged by this hand,

so that Mycenae and Sparta, too, may know

that mother Skyros bears brave men.

PHILOKTETES

Well spoken, boy.

What wrath have they incited in you?

NEOPTOLEMOS

Philoketetes, I will tell you everything,

although it pains me to remember.

When I came to Troy, they heaped dishonor on me,

after Achilles had met his death in battle....

PHILOKTETES

Tell me no more until I am sure I've heard rightly:

is Achilles, son of Peleus, dead?

NEOPTOLEMOS

Yes, dead, shot down by no living man,

but by a god, so I've been told.

He was laid low by Lord Apollo's arrows.

PHILOKTETES

The two were noble, the killer and the killed.

I am not sure what to do now---

to hear out your story or mourn your father.

NEOPTOLEMOS

It seems to me that your woes are enough

without taking on the woes of others.

PHILOKTETES

You speak rightly. Now tell me more,

what they did---that is, how they insulted you.

NEOPTOLEMOS

They came for me in their mighty warships

with painted prows and streaming battle flags.

Odysseus and my father's tutor were the ones.

They came with a story, true or a lie,

that the gods had decreed, since my father had died,

that I alone could storm Troy's walls.

So they said.

You can be sure that I lost no time

in gathering my things and sailing with them,

out of love for my father, whom I wanted to see

before the earth swallowed him.

I had never seen him alive.

And I would be proved brave if I captured Troy.

We had a good wind. In two days we made bitter Sigeion.

A mass of soldiers raised a cheer,

saying dead Achilles still walked among them.

They had not yet buried him.

I wept for my father. And then I went

to the Atreids, my father's supposed friends,

as was fitting, and I asked for my fathe

Font size:

Submitted on August 03, 2020

Modified on March 05, 2023

- 16:08 min read

- 12 Views

Quick analysis:

| Scheme | Text too long |

|---|---|

| Closest metre | Iambic pentameter |

| Characters | 15,977 |

| Words | 3,187 |

| Stanzas | 92 |

| Stanza Lengths | 6, 16, 4, 10, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 1, 2, 9, 2, 4, 1, 29, 6, 11, 6, 1, 2, 2, 1, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 1, 2, 2, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 1, 1, 10, 8, 6, 11, 3, 1, 5, 8, 14, 10, 1, 1, 7, 1, 8, 14, 1, 5, 4, 5, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 3, 1, 15, 8, 8, 18, 11, 4, 2, 3, 3, 3, 2, 4, 2, 3, 3, 2, 2, 13, 7 |

Translation

Find a translation for this poem in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this poem to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"Philoktetes" Poetry.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2024. Web. 10 May 2024. <https://www.poetry.com/poem/56661/philoktetes>.

Discuss the poem Philoktetes with the community...

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In